For me, the best jazz performances have far more in common than widely believed, no matter when they were created. It’s really not that much of a jump from King Oliver to Ornette Coleman, from Ethel Waters to Cecile McLorin-Salvant, or from Bix Beiderbecke to Ambrose Akinmusire.

All the talk about “styles” (need I list them? ) is essentially meaningless once we get beneath the surface of music. Sadly, it remains firmly embedded in the great majority of writing about and also in the teaching of the music itself. I dealt with this in detail in my 2001 book The NPR Curious Listener's Guide to Jazz, and it’s been a main tenet of my teaching and lecturing for decades.

And if you need further convincing, here’s what Sonny Rollins said to Kevin Le Gendre in a 2021 Jazzwise interview:

“We didn’t have any barriers. In other words it wasn’t ‘oh, okay we’re going to play swing… okay, now we’re going to play some bebop… or now we’re going to play some free music.’ No, I think we were playing… there was a love of the big, big picture, jazz, the big picture, not jazz in little styles and different styles. Jazz as the big picture. That’s what we achieved and that’s what we loved. When I got there we all came together, realising that there was a big picture of jazz. There’s a little picture, ‘okay this guy plays cocktail music, this guy is avant-garde, okay that’s fine separating. What we tried to do was not separate… but to bring together all the stuff you mentioned. They were in the air at that time and the so-called ‘free’ stuff, and we tried to unify them, and that is a very important thing in life, unification. That’s what the world is all about, we’re trying to unify things. That’s what we’re trying to do. Unity, unity, unity! That was a very important aspect of those records.”

This blog will consist of two elements:

Examples of music I love for these reasons, along with and various historical documents (interviews/musical samples and the like) coming from this vantage point.

Other things that keep me going - cinema/literature/travel

If you’re interested, please subscribe!

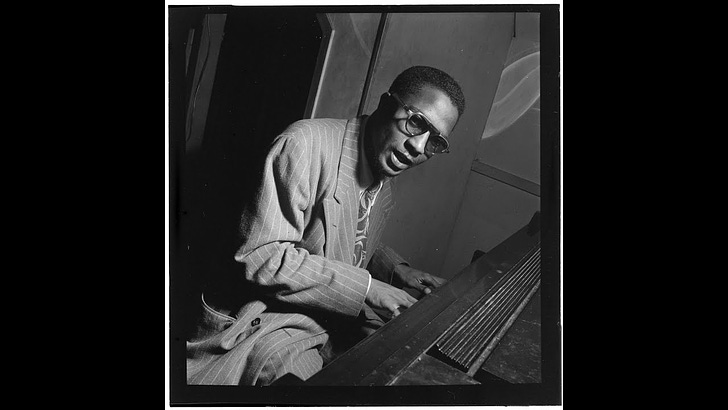

Here’s a wonderful item to kick things off - early, (VERY EARLY) Monk and the his first version of ROUND MIDNIGHT. Much has been made of his relation ship to his mentor James P. Johnson and stride piano in general, but in future posts I’ll be digging into an equally important influence in Monk’s music - Art Tatum.

Dear Mr. Schoenberg, Thanks very much for the posts so far - I’ve got one of a few monthly gift subs, and love the content so far; the major problem for all of us is finding enough time to absorb all this good writing about jazz music!!!

One thing I wanted to add was that I’m reading Dan Morgenstern’s Living with Jazz at the present, and in there he includes a 1958 essay called “Cats and Categories”, which echoes the point that you make concerning pigeonholing into styles. Morgenstern takes Coleman Hawkins (subject of a future post) as a good example: “since leaving the Metropole, Hawk has played at the Sutherland in Chicago, a room generally reserved for ‘modern’ names. Here the ageless master found himself in the company of the Three Sounds, and was pleased, especially with the pianist, Gene Harris. Some weeks later, Coleman had a weekend gig in Pennsylvania and brought along trumpeter Booker Little, recently with Max Roach, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer J.C. Heard.” He then goes on to detail a third gig that followed which included Randy Weston, Roy Haynes, and Kenny Dorham (pp. 1809 - 1811 of the eBook version). A master musician, playing with like-minded masters.

so glad to see you around here. It’s a terrific platform.